The profound response of the Murray-Darling Basin’s ‘river of sand’ to Holocene climate change

Dryland rivers are inherently variable in terms of their hydrology, geomorphology, and ecology across a range of scales. This variability can make it difficult to disentangle long-term change from natural variability and makes it difficult to assess their likely sensitivity to future climate and hydrological changes. By investigating how rivers have responded to periods of climatic change in the past we can better define thresholds that trigger these changes and get a better picture of the ways in which dryland rivers respond to changing climates.

In our recently published research, we investigated the often overlooked Warrego River in the northern Murray-Darling Basin with the aim of characterising it’s modern-day hydrology and geomorphology, and reconstructing its Holocene evolution.

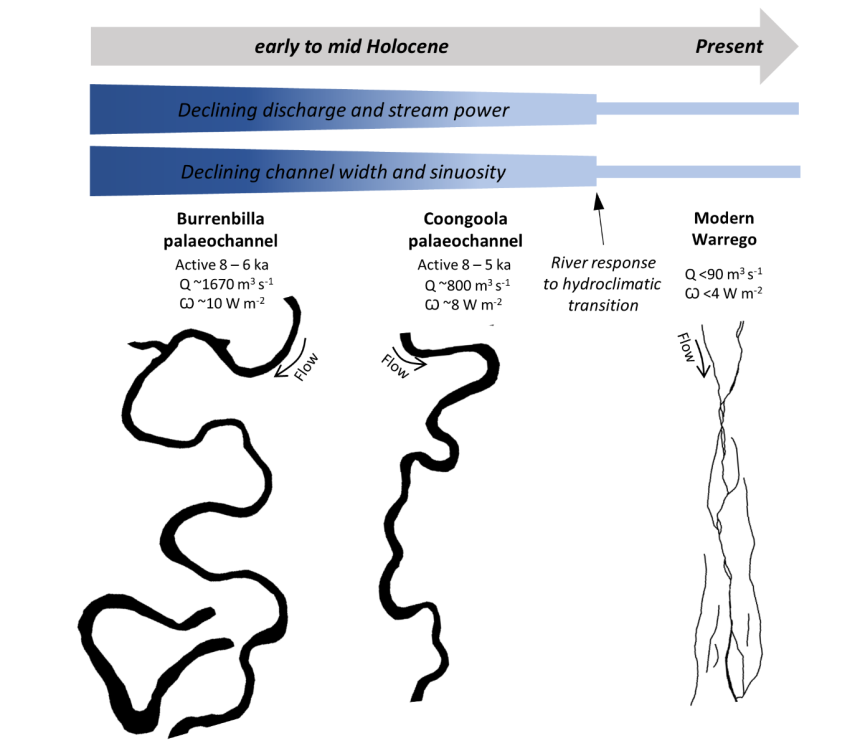

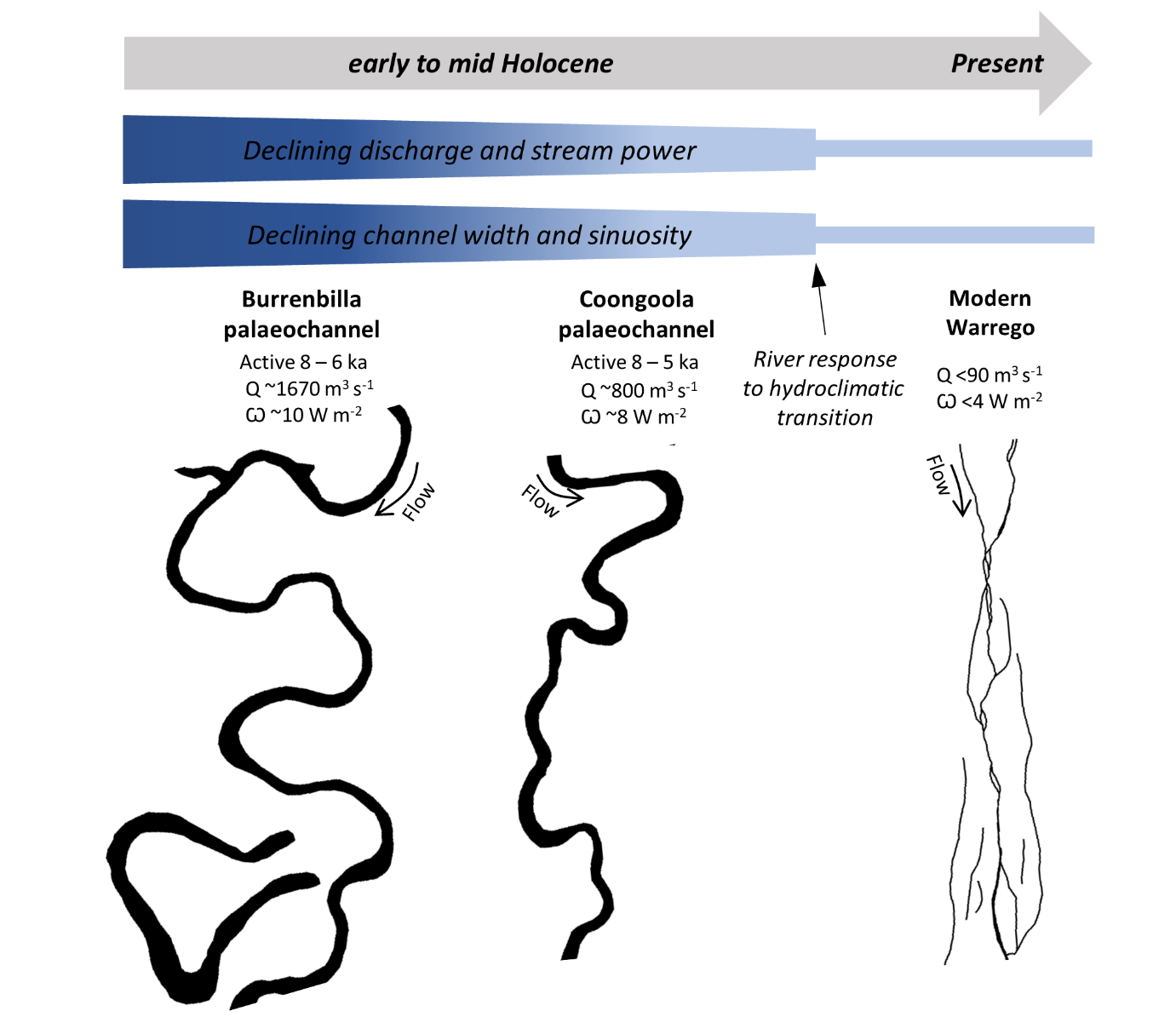

The Warrego (an indigenous Bidjara word meaning ‘river of sand’ and, in some cases, ‘bad’) drains headwater catchments in the Carnarvon Ranges of central QLD, and flows across a large, low-angled alluvial fan before – sometimes – joining the Darling River near Bourke in northern NSW. Today, flow in the Warrego River is highly variable and it persists for much of the time as a string of isolated waterholes with dry channels along most of its length. It is also characterised by periodic but enormous floods that can inundate up to 3,000 square kilometres of intermittent and ephemeral wetlands. Large palaeochannels (ancient, abandoned river courses; named Burrenbilla and Coongoola after nearby localities) preserved on the surface of the floodplain however, indicate that at some stage in the past the Warrego was considerably larger and conveyed much more regular flow. Optically stimulated luminescence dating of these palaeochannels confirms that these large (~160 m wide), meandering channels were active between ~8,000 – 5,000 years ago. They transported about 20-30 times as much water as the modern system does, and the meandering pattern indicates that flow was likely much more regular.

During the mid-Holocene period when these channels were active, the southern oscillation in the Pacific Ocean was in a persistent La Niña-phase leading to increased rainfall over northern and eastern Australia as well as reduced hydrological variability.

After about 4,500 years ago, an increased frequency of El Niño events created much more variability in the climate of eastern and northern Australia, effectively increasing overall aridity. This shift triggered the dramatic, threshold response of the Warrego River whereby it was no longer able to support a large meandering channel and formed the modern pattern of small, relatively straight channels that disintegrate into wetlands on the floodplain. The threshold defining this response seems to be related to stream power (the available energy of flowing water) values dropping below ~6 W/m2. The increased variability of flow likely also had a very significant influence on the step-change in river geomorphology. Given the similarity between mid-late Holocene climate changes in eastern Australia and those projected for coming decades (i.e. increased aridity and variability), obvious questions are raised about how dryland rivers throughout Australia will respond.

More research is needed to fully understand the thresholds defining river response to climatic and hydrological change.

The Burrenbilla and Coongoola channels near Cunnamulla in southwest QLD were active between about 8000-5000 years ago. Note the dramatically different size and morphology of these channels compared to the modern Warrego. Source: Larkin ZT, Ralph TJ, Tooth S, Duller GAT, 2020. A shifting ‘river of sand’: The profound response of Australia’s Warrego River to Holocene hydroclimatic change, Geomorphology, 370, 107385.

Paper: Z.T. Larkin, T.J. Ralph, S. Tooth, G.A.T. Duller (2020). A shifting ‘river of sand’: The profound response of Australia’s Warrego River to Holocene hydroclimatic change, Geomorphology, Volume 370, 107385, ISSN 0169-555X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2020.107385.