Revisiting trends in Australian pan evaporation

Evaporation pans measure atmospheric evaporative demand and are used to estimate water loss from storages such as dams and to provide inputs to hydrologic models and drought indices. In the late 20th century, a surprising trend was found: although temperatures were increasing, pan evaporation was generally decreasing in many parts of the world, including Australia. Pan evaporation responds to four key drivers: net radiation, air temperature, wind speed and vapour pressure deficit. Earlier research, such as that by the Australian National University and the Queensland Government, showed that declining wind speeds (“stilling”) were chiefly responsible for the declining trend in Australia.

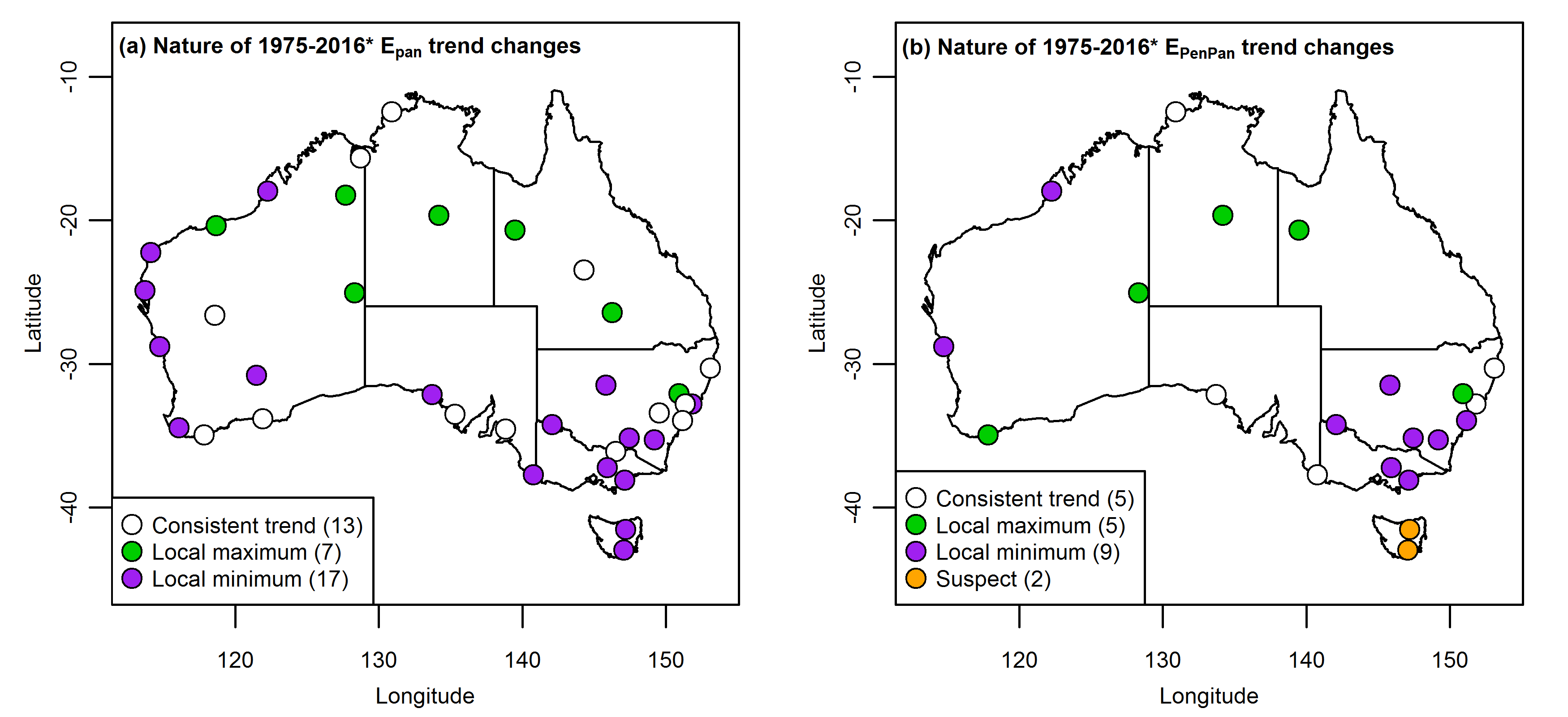

We revisited the conclusions of these studies using an additional 12 years of observations. Interestingly, we found that many previously decreasing pan evaporation trends in western and southern Australia are now increasing. The opposite behaviour was observed in central Australia, where previously increasing trends are now decreasing (Figure a). On average, the inflections in pan evaporation occurred in the early 1990s.

Following Australian researchers at the CSIRO and Australian National University, we used the PenPan model to attribute the observed changes to climatic drivers. The modelled PenPan evaporation showed similar behaviour to the observed pan evaporation (Figure b). A flexible regression technique was applied to locate inflections in the PenPan results and linear regression was applied over appropriate subsets of the data to quantify contributions of different drivers. We showed that the recent increases in pan evaporation in western and southern Australia were due to increasing air temperature driving greater vapour pressure deficits. Possible reasons for increasing air temperatures include anthropogenic climate change and/or a period of drought (2000s) in Australia; both of these factors likely contributed to the increasing pan evaporation trends. In central Australia, wind speed changes were the most common driver of trends in pan evaporation both before and after the inflections, with substantial contributions from vapour pressure deficit in some cases. The switch from decreasing to increasing atmospheric evaporative demand in many populated and agricultural areas may reduce water security due to greater evaporative losses from water storages. We also highlight the need for primary observational networks to be better supported: of the 37 evaporation pans considered in this study, nine have closed since 2004, with substantial parts of the country (including Queensland, the Northern Territory and South Australia) having very limited long-term pan evaporation observations available (Figure a).

Reference: Stephens, C. M., McVicar, T. R., Johnson, F. M., & Marshall, L. A. (2018). Revisiting pan evaporation trends in Australia a decade on. Geophysical Research Letters, 45(20), 11,164–11,172. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL079332.