A global perspective on intermittent river flow regimes

Some rivers flow all year (perennial), others may flow most of the year or only occasionally (intermittent). This flow period and the intensity and volume of the flow define a river’s flow regime. Understanding the flow regime is important because it tells us what ecosystems the river can support and how much water can be extracted for human use. In intermittent rivers, the flow regime is characteristically linked to periods of no-flow, and changes in the number and duration of no-flow events over time give us clues about what impacts we may be having on our rivers, either through water extraction or due to large-scale shifts in rainfall and evaporation.

Globally, climate is known to be a primary driver of flow regime, along with other factors such as geology, topography, and land use. Typically, we study both the flow regime and its drivers using flow records from gauging stations. This data is rapidly becoming available at a global scale, although not always at the locations where scientists would like to know what is going on. Moreover, it can be extremely difficult to find data for rivers considered to still have relatively natural flow regimes; the rivers which give us the best clues about how flow may be changing due to climate.

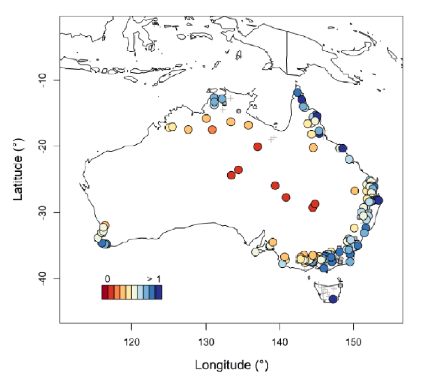

Our recent study used this data to classify rivers and elucidate trends in no-flow events linked to climate change across the U.S., Australia, France, and the UK. Across these four countries, we found that intermittent rivers are under-represented in the hydrological data of most countries; even in Australia, gauging stations are disproportionately located on perennial rivers. Aridity, a measure of dryness, was found to be the most important dryness of flow regimes overall. Although this factor cannot explain the presence of intermittent rivers in humid regions such as the UK, where geology plays a strong role.

Importantly, we found that droughts were readily apparent in the flow records of intermittent rivers in all countries. At the global scale, the global warming observed in recent years may not necessarily have led to more flow intermittence; however, a definite upward trend in the number of days that rivers do not flow was observed for several stream classes. This includes several stream classes found in northern Australia.To better monitor this trend into the future more data is needed on intermittent rivers. Evolving methodologies such as citizen science initiatives and remote sensing may help to fill the data gap.