Hasta la vista El Niño – but don’t hold out for ‘normal’ weather just yet

Australia’s rainfall is perhaps the most variable of any continent on Earth. When averaged across the country, rainfall in 2015 was only slightly below normal. However, there were large areas of both extreme dry and relative wet across Australia and throughout the year.

Last year’s weather was dominated by one of the strongest El Niño events on record, contributing to high temperatures, reduced rainfall and devastating bushfires in Australia.

Observations from the Pacific show that El Niño has likely peaked, with models predicting its demise over the coming months. So does this mean the weather will return to “normal”?

The oceans around us

El Niño and its sister La Niña are the most significant cause of year-to-year climate variation for Australia and the Pacific region. In simple terms, these events describe the east-west movement of the warmest water in the tropical Pacific Ocean — and the accompanying shift in rainfall patterns.

In 2015, El Niño arrived in May and developed into one of the strongest such events on record, comparable to those of 1982-83 and 1997-98. Seventeen of the 26 El Niño events since 1900 have brought widespread dry conditions to Australia, so it is unsurprising that some areas have suffered in the past year.

While there is now a general appreciation of the connection between El Niño and drought, the impact on Australia depends on what happens in the Indian Ocean at the same time. In southern Australia, the drying influence of El Niño is most obvious when it combines with particular sea surface temperature patterns to Australia’s west.

This pattern is known as the Indian Ocean Dipole. Like El Niño in the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean Dipole is related to the east-west movement of warm water in the tropics. When the dipole is positive (cooler than average water closer to Australia, warmer off the coast of Africa), central and southeast Australia often see drier conditions, particularly in spring. When a positive Indian Ocean Dipole combines with an El Niño event we tend to see very dry conditions in Australia.

During 2015, sea surface temperatures in the Indian Ocean likely helped offset the impact of El Niño in winter, but reinforced its drying influence in spring.

In autumn, as the 2015 El Niño strengthened in the Pacific, a broad swathe of the Indian Ocean was also warming up, particularly to the southwest of Australia. This appears, at least in part, to have contributed to more late autumn and winter rainfall than may be expected in a typical El Niño year. Individual weather systems brought rainfall from the west over Western Australia, New South Wales, and eastern Victoria during this time.

By spring, the pattern of sea surface temperatures shifted. Relatively cooler waters developed in the Indian Ocean south of Indonesia — creating a positive Indian Ocean Dipole that cut off the moisture from the west, and dramatically reinforced the drying influence of El Niño to Australia’s east.

As a result, Australia recorded a September-October rainfall of just 17 mm — the third-lowest total on record. The switch from near-normal national rainfall to very dry conditions was rapid. It then reversed a second time, bringing above-average rains to parts of Australia across November and December.

Meanwhile on land, October broke the record not only for the warmest October, but also for the largest margin by which a monthly temperature record has ever been broken. The particularly dry and hot September and October led to substantial impacts on Australian agriculture, including significant downgrades of winter crops.

It also set the scene for an early and severe start to the southern bushfire season. At the start of October South Australia, Victoria and Tasmania experienced a heatwave and fire weather more typical of early summer. For Tasmania, fire weather reached catastrophic levels at a time of the year when, historically, it would be rare to record even extreme fire ratings.

The 2015 El Niño has now passed its peak. Northern and eastern Australia will likely see better rainfall, particularly if 2016 brings a La Niña event later in the year. Regardless, many past El Niño events have seen better rainfall in the year that they break-down, providing hope for those looking to drought relieving rain

Longer-term changes

The past year has highlighted that Australia continues to experience a range of natural and human-induced changes to its climate.

On decadal timescales, by far the biggest influence on rainfall across the south of the continent has been long term changes in atmospheric circulation. These changes have led to drying in the cooler months of the year across the southwest and southeast — associated with reduced rainfall from westerly winds and cold fronts — consistent with climate change.

Southwest Australia rainfall has declined by 10-20% since the 1970s, while southeast Australia has experienced similar declines since the 1990s.

However, on shorter timescales, the pattern of sea surface temperatures is still important for Australia. While the long-term trend is for less rainfall, individual seasons will still be wet when conditions are favourable — such as the concurrent occurrence of a La Niña and relatively warm waters in the Indian Ocean.

In 2015, the start of El Niño exacerbated pre-existing drought over northeast Australia. Queensland, for example, has been dry since the wet season failed in the summer of 2012. The impacts of low rainfall have been increased by unusually high temperatures, with Queensland experiencing its warmest three-year period on record.

As the year went on, drought conditions spread across far southern Australia. These are the areas that have seen that long-term rainfall decline. These southern regions were also some of the most-affected by the “Millennium Drought”, which started around 1997 in southern Australia, and is generally considered to have ended in the La Niña of 2010.

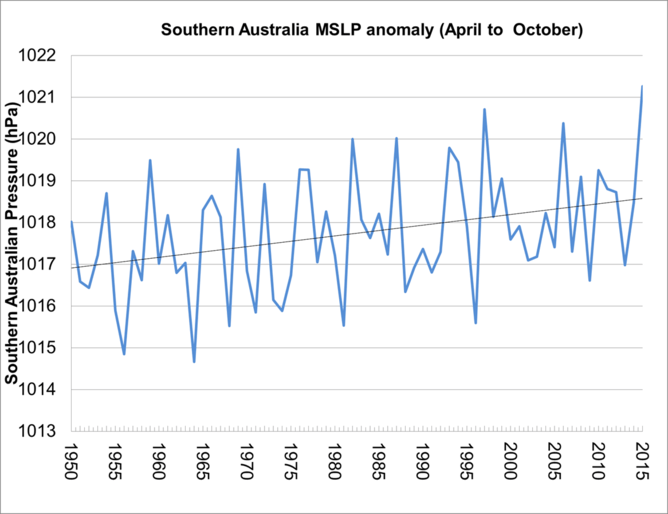

2015 showed the atmospheric circulation and rainfall pattern that has become common during recent decades, and was a big part of the Millennium Drought. High-pressure systems — which bring clear skies and dry conditions — dominated southern Australia throughout the year. Ultimately, 2015 saw the highest average pressure ever recorded for the southern cool season.

Studies have linked this trend to increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, with a warmer world seeing an expansion of the subtropical arid regions towards the poles.

The drying has affected the major catchments for Melbourne, Adelaide, Hobart and Perth, cities which all experienced an unusually dry 2015. These southern cities, including those well known for their cool, wet winters, have been far less wintery. Current long-term rainfall deficiencies in places such as Victoria are as severe as at any time during the Millennium Drought, with 2015 adding to this drying pattern.

Those sensitive to rainfall conditions such as in agriculture, emergency services and water managers should plan for dry conditions being more the norm, rather than the exception in these parts.

Original article posted on The Conversation, 28 January 2016 (Link)