Not just heat: even our spring frosts can bear the fingerprint of climate change

In recent years, scientists have successfully identified the human fingerprint on hot years, heatwaves, and a range of other temperature extremes around the world. But as everyone knows, climate change affects more than just temperature.

The “signal” of human-induced climate change is not always clear in other weather events, such as cold snaps or episodes of extreme rainfall.

Three new studies, released today as part of a special edition of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, take a closer look at two such events, both of which happened in southern Australia in mid-2016: the frosts that hit Western Australia’s South West, and the extremely wet weather that hit much of southeastern Australia during that year’s winter and early spring.

Perhaps surprisingly, WA’s frosts showed a fingerprint of climate change, due to changes in weather patterns. Meanwhile, there was very little climate change signal in the extreme rainfall that hit the southeast.

While there is a clear human-driven upward trend in Australia’s average temperatures and the future of southern Australia is projected to be dry in the cool seasons, last year Australia experienced its wettest winter and September on record. Meanwhile, September in WA’s South West brought up to 18 frost nights across the region – the most on record in some locations.

An increasing temperature trend would limit the number of extreme cold events, and broadly speaking this is true for Australia. So what caused the record frost risk in South West WA in September 2016?

For the northern hemisphere, a “wobbly” jet stream has been proposed as the cause of periodic blasts of extreme cold weather. In this theory, human-driven changes to atmospheric circulation cause Arctic air to temporarily extend southwards over populated areas, bringing Arctic weather in spite of the background warming trend. But this kind of theory hasn’t been examined in depth for Australia.

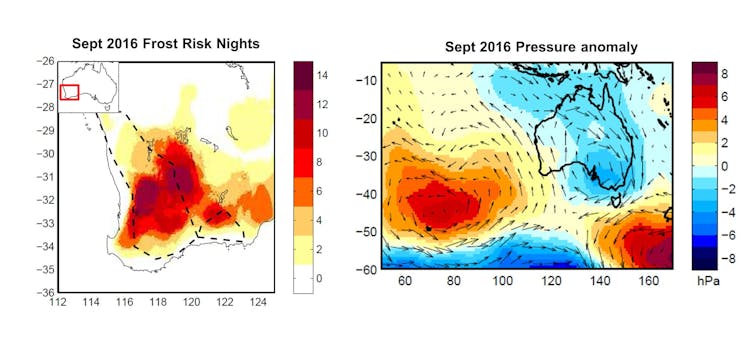

During southwestern WA’s bout of September frosts, the atmospheric pressure was generally very high, and the skies were clear. What’s more, that month featured a particularly persistent weather pattern of slow-moving high pressure west of Australia, which brought in cold air from the south.

The question is whether human-induced climate change is altering the circulation to make these conditions more likely. Research led by Michael Grose addressed this question by comparing climate models that describe the current, human-altered climate, and ones that leave out the influence of human-produced greenhouse gases.

Their results suggest that human-induced climate change is indeed changing the circulation patterns in our region, making this particular pattern more likely. They also suggest that it’s a fine balance between increasing average temperatures and these altered circulation patterns in this part of Australia.

In the models, daily minimum temperatures were not colder in the current climate than in those models without a human influence. This suggests that the two effects may cancel out (as far as extreme frost is concerned), although more work is needed to understand this intriguing possibility.

Record wet winter

Raising the global temperature can also make air more humid and therefore can result in more extreme rainfall events. The wettest day of the year is projected to become wetter by the end of the century. Are we already seeing an increase in extreme rain, and does it also hold true over the course of a month or a whole season?

September 2016 was by far the wettest September on record in Australia’s southeast, including the Murray Darling Basin, Australia’s food bowl. The amount of moisture in the air column during that month was extremely high. The question is whether this could have happened in a climate without global warming.

Researchers led by Pandora Hope analysed the local conditions for rainfall generation in forecasts of the event, under both the current climate and in a model that did not feature human greenhouse emissions. Air moisture levels were very high in both forecasts, but no higher in the current human-influenced climate than it might otherwise have been.

But there is more to rain generation than simply how much moisture there is in the air. Other factors are also important, such as weather patterns that cause moist air to accumulate in certain areas, and local atmospheric instability which is important for storms to form.

September’s rain brought flooding to many parts of New South Wales. AAP Image/Anita Redfern

The results showed that under current climate conditions, those circulation factors were not as favourable to producing rainfall as they would be in a world without increased levels of carbon dioxide.

In other words, the local environment is generally becoming more stable, so it will be harder for these sorts of extreme rainfall events to develop.

During July to September 2016 the eastern tropical Indian Ocean was extremely warm, a result of the coincidence of the year-to-year variability of the tropical oceans and a strong ongoing upward warming trend. Rainfall in southeast Australia is often increased when ocean temperatures to the northwest of Australia are unusually high.

Research by Andrew King found that this association is indeed strong, and very important for the heavy rainfall through these months in 2016. But by analysing climate models both with and without the human influence on the climate, he found that human forcing had little influence on the intensity of this extreme rain event, consistent with the findings of the other study described above.

There is clearly still much left to learn about attributing the causes of extreme weather events. But these studies show that examining the effects of climate change on atmospheric circulation can help us better understand humans’ influence on Australian weather extremes.

Original article posted on The Conversation, December 14, 2017 (link)