After a record dry, 2018 may be the year of the Indian Ocean Dipole

The droughts of past decades have burnt the term El Nino into the Australian vocabulary, but after the drought of 2018, perhaps the IOD — short for Indian Ocean Dipole — might also become a household name.

A decade ago, an Australian team led by a young climatologist, Caroline Ummenhofer, began trawling through more than 100 years of Australian drought records.

The conventional thinking was that El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) drove Australia’s drought cycle.

But the University of New South Wales team was looking for a different culprit, and at the turn of the millennium, a new climate driver was discovered — the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD).

It worked a lot like El Nino, but on the western side of the country in the Indian Ocean.

Dr Ummenhofer discovered the IOD was an even bigger factor than El Nino in driving long-term Australian droughts.

“The Indian Ocean is as important to Australian rainfall as the Pacific Ocean is,” Dr Ummenhofer said.

“When you’re looking at prolonged drought periods, particularly the millennium drought or the earlier droughts that Australia has experienced, it’s actually more the Indian Ocean that is in an unusual state, particularly Indian Ocean Dipole events occurring in unusual numbers.”

Dr Ummenhofer’s work on the IOD changed the way drought in Australia is understood and helped propel the climatologist to the top of her field.

She now runs her own lab at the prestigious Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts in the United States.

IOD drove the spring climate

In its summer outlook the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) said the IOD is currently dominating Australia’s weather and climate patterns.

This comes after Australia experienced its driest September on record.

BOM climatologist Jonathan Pollock said it is likely the IOD has outweighed El Nino in driving this year’s dry.

“While we’ve seen development towards an El Nino in the Pacific, we’re not there yet,” Mr Pollock said.

“But we have had a positive Indian Ocean Dipole event.”

Dr Caroline Umenhoffer said the strongest droughts and floods Australia experiences are when the IOD combines with ENSO.

“When you have the synergies of both ocean basins working together, that is when you’re getting the biggest signals on the drought side and on the flood side.”

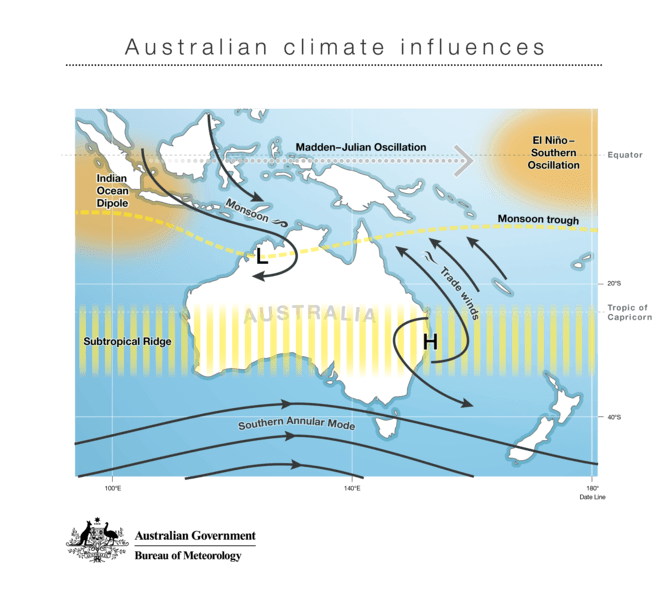

The Australian climate is driven by surrounding oceans

Each of the three oceans surrounding Australia has a key climate driver.

ENSO looks at the Pacific Ocean, the Southern Annular Mode looks at the Southern Ocean, and the IOD looks at the Indian Ocean.

These big three are the main tools climatologists use to predict Australia’s long-term climate outlooks.

Like El Nino, the IOD describes differences in temperatures from one side of an ocean to the other.

And like El Nino, these differences in ocean temperatures drive rainfall patterns.

Australia’s rain originates in the oceans, so to understand why rains fail, you need to look out to sea.

Broome’s butterfly effect

It might seem a long way from drought affected NSW, but incredibly, the seas off Broome affect whether the eastern states get rain.

The Indian Ocean between Western Australia’s north and Indonesia is a source of moisture, evaporating into the air and rising into the upper atmosphere.

When these waters are warmer than average, moisture bearing winds bring more rain to Australia, which is known as a negative IOD event.

When moisture from the seas off Australia’s north-west connect with winter storms to the south, north-west cloud bands can form, sometimes bringing rain right across the country, from Broome all the way to Hobart.

But for much of this year, the Indian Ocean off WA was cooler than average, which is referred to as a positive IOD event.

Cooler waters lead to weaker, drier winds and less rainfall, which is why the IOD has been linked to the drought Australia has experienced in 2018.

ENSO and the IOD

BOM senior climatologist Greg Browning watches the IOD and ENSO to help predict the onset of the northern monsoon.

He has recently observed the warming of waters off WA.

“With perhaps the grip of this IOD weakening, it’s probably one of the factors that’s helping to lessen the rainfall deficiencies in the past few months,” Mr Browning said.

No matter how strong the pattern, every summer the IOD decays as it is overwhelmed by the monsoon.

“That now becomes the main driver, and that pretty much has a life of its own,” Mr Browning said.

“As the IOD goes, it’s going to have less of an impact over Australia.

“All bets are off and the monsoon is the main deal in town.”