Floods don’t occur randomly, so why do we still plan as if they do?

Most major floods in South East Queensland arrive in five-year bursts, once every 40 years or so, according to our new research.

Yet flood estimation, protection and management approaches are still designed on the basis that flood risk stays the same all the time – despite clear evidence that it doesn’t.

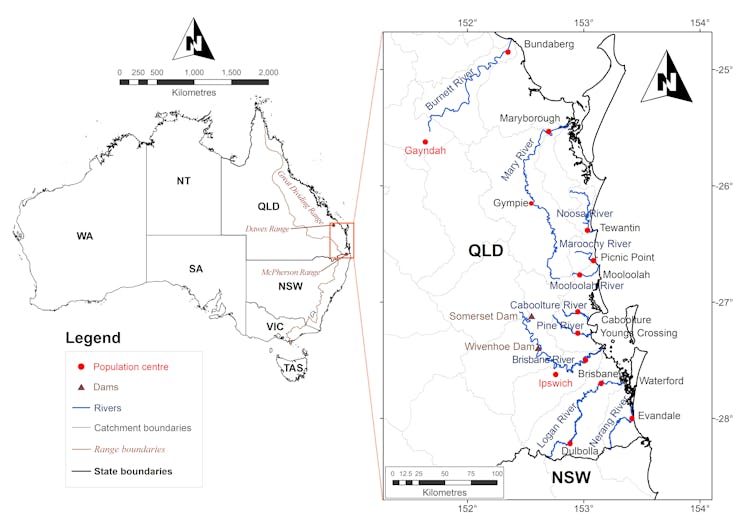

We analysed historical flooding data from ten major catchments in South East Queensland. As we report in the Australasian Journal of Water Resources, 80% of significant floods arrived during five-year windows, with 35-year gaps of relative dryness between.

The early 1970s brought a succession of severe floods to South East Queensland. This was followed in the 1980s by a raft of floodplain development projects, together with extensive research on floodplains and flooding risk, carried out by a group of researchers who described themselves as the “Roadshow” because of their frequent visits to flood-prone regions.

Throughout the 1980s, some Roadshow members noticed that large floods in South East Queensland seemed to follow a 40-year cycle, with five-year periods of high flood risk separated by 35 years of lower flood risk. They speculated that the next “1974 flood” (a reference to a devastating flood that hit Brisbane and South East Queensland that year) would arrive some time around 2013 .

Sure enough, South East Queensland was once again hit by large floods in January 2011 and January 2013.

Evidently, large floods in South East Queensland are not random. This is a problem, given that development policies and engineering practice, by and large, still assume that they are.

History repeating

In 1931, the Queensland meteorologist and farmer Inigo Jones linked the Brisbane River’s floods to the Bruckner Cycle of solar activity, which he determined to be 35 years long, but which has since been found to vary from 35 to 45 years.

In 1972, flood engineer John Ward argued that flood frequency distributions differ in space and time because higher flows originate from a variety of different rainfall mechanisms. At the time, minimal insight was available into what those different rainfall mechanisms were.

In the 1990s, drought research in Queensland by, among others, researchers Roger Stoneand Ken Brook and John Carter identified cyclical variations in Queensland rainfall associated with the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), supporting the idea of non-random occurrence of floods.

In 1999, Australian hydrologist Robert French also noticed that irregular clustering of flood events was associated with the SOI, and pointed out that flood planning needed to take into account more than just seasonal or year to year variability.

More recently, flood incidence has been strongly linked to large-scale ocean processes such as the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO). These phenomena seem to have a marked effect on eastern Australian rainfall variability, and therefore on the risk of both floods and drought.

Is the 40-year cycle real?

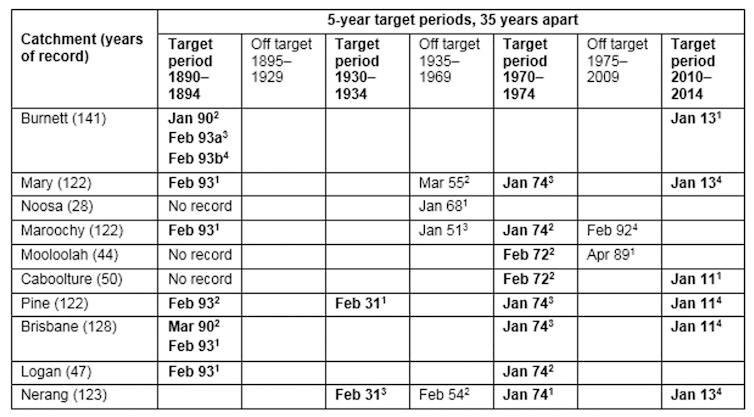

We compiled records of major floods in South East Queensland between 1890 and 2014. As the table below shows, roughly 80% of large historical floods happened within a series of five-year flood-prone periods, despite these periods together representing only 16% of the study period.

Timing of the largest flood events within the 40-year cycles. Superscripts next to each flood event indicate the ranking of that flood event in that catchment (that is, the largest flood in each catchment is ranked 1).

On average, the number of large floods per year was 4.9 times higher within the five-year flood-prone periods.

Not only were floods more frequent, they were also more severe, with flood heights 41% higher during the five-year flood-prone periods than at other times.

Even though a few large floods occurred outside the five-year flood-prone periods, the 40-year cycle of flooding in South East Queensland appears to be a genuine phenomenon.

What drives the cycle?

The most likely physical explanation for cyclic or non-random flooding is the IPO, which is rather like the ENSO cycle except on longer time scales. The IPO influences eastern Australia’s climate indirectly, by affecting both the magnitude and frequency of ENSO impacts.

Recent “negative phases” of the IPO – meaning warmer than average Pacific Ocean temperatures north and south of the tropics – happened roughly during 1870–95, 1945-76, and 1999–present.

If we compare these with the five-year flood-prone periods in the table above, we can see that with the exception of 1930–34, all five-year flood-prone periods happened during these negative IPO events. Interestingly, the large floods in the 1950s and 1960s happened outside the five-year flood-prone periods identified by the 1980s Roadshow, but do align with IPO negative conditions.

In spite of all this evidence, most engineers and flood planners still assume that floods occur randomly and that flood risk is the same all the time. Phrases like “one in 100-year event” or “1% annual exceedance probability” are routinely used to describe floods, despite the fact that for some years and decades the risk is significantly higher. This gives a false sense of security during times when major floods are much more likely.

If this approach continues, then every few decades our flood defences will not be as reliable as we thought – a fact to which many Queenslanders can now attest.

We need new approaches to deal with the reality that large flood events do not occur randomly. It would arguably be more sensible to separate flood records into two (or more) categories – one for times when flood risk is “normal” and another for periods where the risk is higher – and then reevaluate flood frequency distributions and flood risks for each category. Decision makers then get a more realistic estimate of the true risk of flooding which leads to more informed and more resilient flood planning and defences.

This new approach might also help plan for the changes to flood risk expected in the future, whether from climate change, land use change, or whatever else the oceans and skies throw at us.

This article was coauthored by Greg McMahon, a Brisbane-based independent consultant on flood risks and Academic Chair at Rhodes Group Australia.

Original article published in The Conversation, March 19, 2018 (link)