Reconstructing Victoria’s streamflows on a catchment scale

Current climate projections indicate that Victoria is heading towards a warmer and drier environment, which will have severe impacts on the state’s water supply.

A recent study by Sonya Fiddes and her colleagues found that by the end of this century severe droughts will see catchment streamflows across Victoria reach levels 30% to 80% worse than that experienced during the Millennium Drought. The study also found that the variability of catchment streamflows across the state, during the Millenium Drought, was mainly due to the catchment’s physical characteristics and pre-existing climate rather than rainfall variability.

The recent Millennium Drought (1997-2009) provided a forewarning for what might become the new norm in terms of water scarcity. For these reasons it has become ever more important to understand how individual water catchments behaved during the considerable stress of the Millennium Drought, and to be able to replicate this behaviour in models.

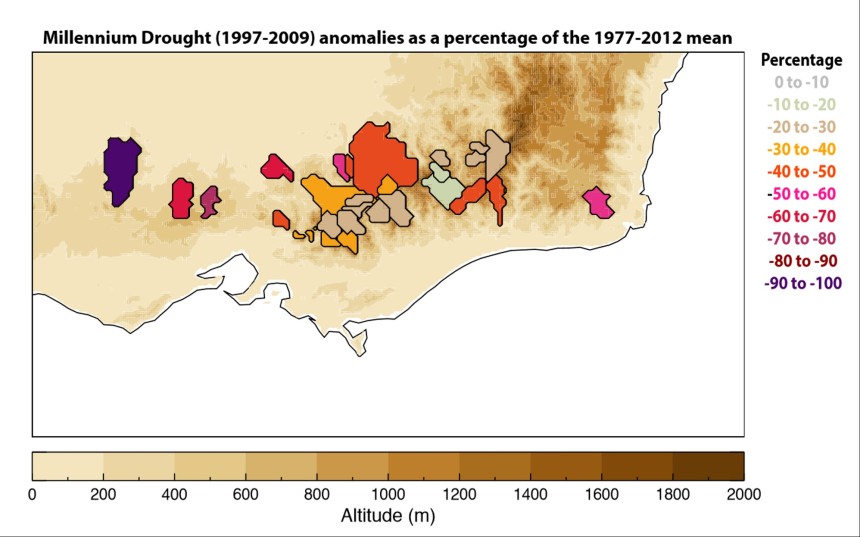

“Our study, ‘Assessment and reconstruction of catchment streamflow trends and variability in response to rainfall across Victoria, Australia’ begins to pick apart the differing characteristics of 27 key catchments across the state.” said the authors.

The research found that drier catchments in the far west of Victoria and towards the east, experienced considerable reductions in streamflows. Some of these catchments saw streamflow reductions of up to 90%, whilst wetter catchments in the vicinity of the Great Dividing Range were somewhat protected from the drought’s affects, with reductions as little as 14%.

According to the authors “the important thing is that this variability across the state is predominantly due to the catchment’s physical characteristics and pre-existing climate; the variability of rainfall across the state over the same time was relatively small, with just a 13% decline on average over the 27 catchments during the Millennium Drought. This is known as the catchment’s elasticity factor, which as other studies have shown is non-stationary, and can become greater under prolonged stress.”

After building an understanding of how these catchments behaved during the Millennium Drought, the researcher team then built a statistical model to reconstruct monthly streamflows, with the goal of applying it to rainfall and temperature climate projections. An important advantage of this work was the use of high-resolution gridded (5km x 5km) rainfall and temperature observational data, and the quick computational time of a simple model. Using this process the researchers could capture monthly streamflows to a high degree, reproducing the drought anomalies and historical trends satisfactorily.

After using this method to reproduce historical trends, the team then applied this model, for the first time, to statistically downscaled climate projections (on the same 5km x 5km grid as the observations), giving an unprecedented look into how individual catchments may behave under a warming climate.

“This work is currently under review but preliminary results indicate that by the end of the century severe droughts will see catchment streamflows reach levels 30% to 80% worse than that experienced during the Millennium Drought.”

The authors also said that, whilst the methods in this work are relatively simple, the use of the downscaled climate data provides a great advantage in capturing specific regional responses. This information, once available, can aid local water authorities and decision makers when planning for their water futures, and is also a great tool in helping communities understand what is happening on their doorstep.

‘Assessment and reconstruction of catchment streamflow trends and variability in response to rainfall across Victoria, Australia’, Climate Research, doi:10.3354/cr01355