‘Tennis ball bounce’: Record low bird numbers highlight water system woes

The number of waterbirds across eastern Australia’s wetlands hit another record low this year as dams and other projects in the Murray-Darling Basin undermined river health, a leading ecologist says.

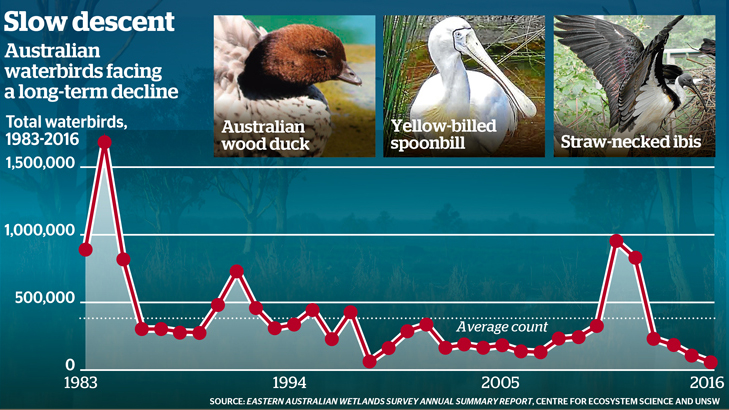

The 34th annual aerial survey counted 71,993 birds in as many as 2000 wetlands and rivers, the least since it began in 1983. The average over these years is 393,000.

The waterbirds of the Macquarie Marshes

For over 30 years, Professor Richard Kingsford from UNSW’s Centre for Ecosystem Science has visited the waterbirds of NSW’s Macquarie Marshes.

A record wet winter and early spring across much of the region will produce some recovery in numbers next year, said Richard Kingsford, professor of environmental science at the University of NSW who has participated in the past 31 surveys and clocked up at least 250,000 kilometres of flying above the wetlands.

Using the analogy of a bouncing ball, the resurgence will be less like a super ball that recovers almost to the height it was dropped but rather that of a tennis ball with its rapidly diminishing rebound, he said.

“Over the past 30-odd years, because we’re getting less frequent flooding – and not for as long in the Murray Darling Basin in particular – we’re seeing the effect of waterbirds not coming back to the same levels they were,” said Professor Kingsford.

(See chart below of bird numbers, measured against the 1983-2016 average.)

The process would worsen if Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce got his way and arbitrarily cut the amount of water set aside for the environment in the northern basin from 390 gigalitres a year to 320 gigalitres, he said.

Measuring up: birds in the Macquarie marshes. Photo: Nick Moir

Aircraft are flown less than 50 metres above the wetlands, with observers on board estimating bird numbers as they go. The planes cover 10 bands, each 30 kilometres wide, across the nation’s east to obtain representative estimates.

The survey calculated that the area of wetlands totalled 235,403 hectares in 2016. That’s up from last year but still more than 10 per cent below the average over the past 34 years, even with the exceptionally wet winter.

Winging it: The Macquarie Marshes had a flood this year – just not a very big one. Photo: Nick Moir

Professor Kingsford said a conservative estimate of the loss of wetlands compared to pre-European settlement was at least 70 per cent, with most of the reduction coming since the middle of the 20th century.

In recent decades, developments on rivers flowing into the Darling River in NSW and Queensland, such as the Gwydir, Lachlan and Condamine-Balonne rivers, had been the most destructive for the wetlands.(See chart below, with the average at about 265,000 hectares.)

Richard Kingsford from UNSW has conducted 31 annual wetland bird counts. Photo: Peter Rae

Projects to create huge water storages at farms – such as Cubby Station in southern Queensland with its 28km-long dams – were of little attraction for water birds.

“Even though there’s lots of water in those places, the birds don’t go anywhere near them because they’re too deep,” Professor Kingsford said.

This year’s good rains were welcomed by farmers and naturalists alike but despite their scale, the benefit to breeding birds in key wetlands such as the Macquarie Marshes might not be significant.

“Even though there’s a good flood there, it’s not a huge flood, and it’s tight in terms of timing and the dry-back of water in the system,” Professor Kingsford said.

“We know that a vast amount of river red gums, coolibah trees are going to die if they don’t get enough flooding.”

The health of the rivers will be stressed further as climate change brings higher temperatures and increased evaporation to what are already arid regions.

“It’s narrowing the opportunity in time that these birds can go through their normal cycle of breeding,” he said.

(See chart below showing how the rainfall over the April-November period compared to long-run averages.)

Among the species facing decline were black swans, small waders and the Australian wood duck.

Another of particular interest to farmers was the straw-necked ibis, which picks off locusts in great numbers, helping to reduce the need for chemical controls.

There are a host of other reasons why river health was important to maintain, Professor Kingsford said.

“We know that as the water level gets lower, the water quality decreases, we get increased algal blooms and increasing salinity,” he said. “The water actually won’t be useful even for irrigation at some point in the future.”

Original article posted on the Sydney Morning Herald website, 17th December 2016 (Link)