2016 is set to be the world’s hottest year on record. According to the World Meteorological Organization’s preliminary statement on the global climate for 2016, global temperatures for January to September were 0.88°C above the long-term (1961-90) average, 0.11°C above the record set last year, and about 1.2°C above pre-industrial levels.

While the year is not yet over, the final weeks of 2016 would need to be the coldest of the 21st century for 2016’s final number to drop below last year’s.

Record-setting temperatures in 2016 came as no real surprise. Global temperatures continue to rise at a rate of 0.10-0.15°C per decade, and over the five years from 2011 to 2015 they averaged 0.59°C above the 1961-1990 average.

Giving temperatures a further boost this year was the very strong El Niño event of 2015−16. As we saw in 1998, global temperatures in years where the year starts with a strong El Niño are typically 0.1-0.2°C warmer than the years either side of them, and 2016 is following the same script.

Global temperature anomalies (difference from 1961-90 average) for 1950 to 2016, showing strong El Niño and La Niña years, and years when climate was affected by volcanoes. World Meteorological Organization

Almost everywhere was warm

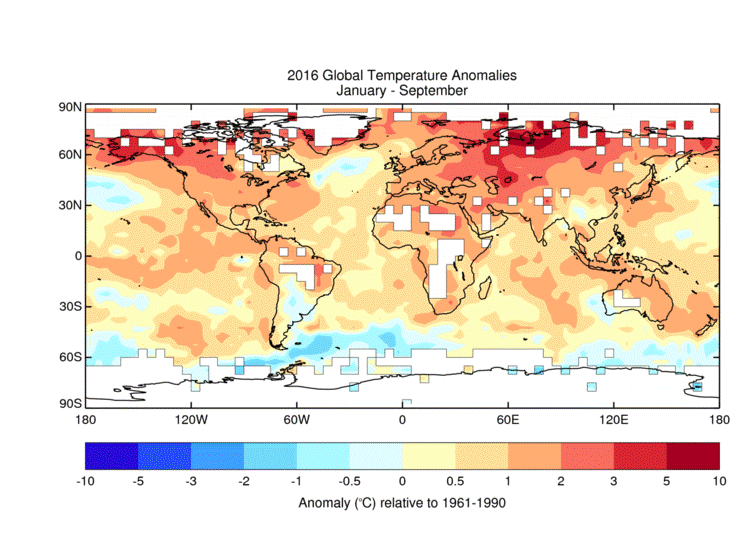

Warmth covered almost the entire world in 2016, but was most significant in high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. Some parts of the Russian Arctic have been a remarkable 6-7°C above average for the year, while Alaska is having its warmest year on record by more than a degree.

Almost the whole Northern Hemisphere north of the tropics has been at least 1°C above average. North America and Asia are both having their warmest year on record, with Africa, Europe and Oceania close to record levels. The only significant land areas which are having a cooler-than-normal year are northern and central Argentina, and parts of southern Western Australia.

The warmth did not just happen on land; ocean temperatures were also at record high levels in many parts of the world, and many tropical coral reefs were affected by bleaching, including the Great Barrier Reef off Australia.

Global temperatures for January to September 2016. UK Meteorological Office Hadley Centre

Greenhouse gas levels continued to rise this year. After global carbon dioxide concentrations reached 400 parts per million for the first time in 2015, they reached new record levels during 2016 at both Mauna Loa in Hawaii and Cape Grim in Australia.

On the positive side, the Antarctic ozone hole in 2016 was one of the smallest of the last decade; while there is not yet a clear downward trend in its size, it is at least not growing any more.

Global sea levels continue to show a consistent upward trend, although they have temporarily levelled off in the last few months after rising steeply during the El Niño.

Droughts and flooding rains

El Niño was over by May 2016 – but many of its effects are still ongoing.

Worst affected was southern Africa, which gets most of its rain during the Southern Hemisphere summer. Rainfall over most of the region was well below average in both 2014-15 and 2015-16.

With two successive years of drought, many parts are suffering badly with crop failures and food shortages. With the next harvests due early in 2017, the next couple of months will be crucial in prospects for recovery.

Drought is also strengthening its grip in parts of eastern Africa, especially Kenya and Somalia, and continues in parts of Brazil.

On the positive side, the end of El Niño saw the breaking of droughts in some other parts of the world. Good mid-year rains made their presence felt in places as diverse as northwest South America and the Caribbean, northern Ethiopia, India, Vietnam, some islands of the western tropical Pacific, and eastern Australia, all of which had been suffering from drought at the start of the year.

The world has also had its share of floods during 2016. The Yangtze River basin in China had its wettest April to July period this century, with rainfall more than 30% above average. Destructive flooding affected many parts of the region, with more than 300 deaths and billions of dollars in damage.

Europe was hard hit by flooding in early June, with Paris having its worst floods for more than 30 years.

In western Africa, the Niger River reached its highest levels for more than 50 years in places, although the wet conditions also had many benefits for the chronically drought-affected Sahel, and eastern Australia also had numerous floods from June onwards as drought turned to heavy rain.

Tropical cyclones are among nature’s most destructive phenomena, and 2016 was no exception. The worst weather related natural disaster of 2016 was Hurricane Matthew. Matthew reached category five intensity south of Haiti, the strongest Atlantic storm since 2007. It hit Haiti as a category 4 hurricane, causing at least 546 deaths, with 1.4 million people needing humanitarian assistance. The hurricane then went on to cause major damage in Cuba, the Bahamas and the United States.

Other destructive tropical cyclones in 2016 included Typhoon Lionrock, responsible for flooding in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea which claimed at least 133 lives, and Cyclone Winston, which killed 44 people and caused an estimated US$1.4 billion damage in Fiji’s worst recorded natural disaster.

Arctic sea ice extent was well-below average all year. It reached a minimum in September of 4.14 million square kilometres, the equal second smallest on record, and a very slow autumn freeze-up so far means that its extent is now the lowest on record for this time of year.

In the Antarctic, sea ice extent was fairly close to normal through the first part of the year but has also dropped well below normal over the last couple of months, as the summer melt has started unusually early.

It remains to be seen what impact the summer of 2016 has had on the mountain glaciers of the Northern Hemisphere.

While 2016 has been an exceptional year by current standards, the long-term warming trends mean there will be more years like it to come. Recent research has shown that global average temperatures which are record-breaking now are likely to become the norm within the next couple of decades.