After a summer of extremes, here’s what to expect this autumn

The past Australian summer was a season of two contrasting halves. So did the midsummer weather change make a dent in the drought, and is it likely to continue through autumn?

The first half of summer was exceptionally hot, dry and dusty. Parts of eastern and southern Australia were engulfed by significant bushfires, and smoke haze covered large areas.

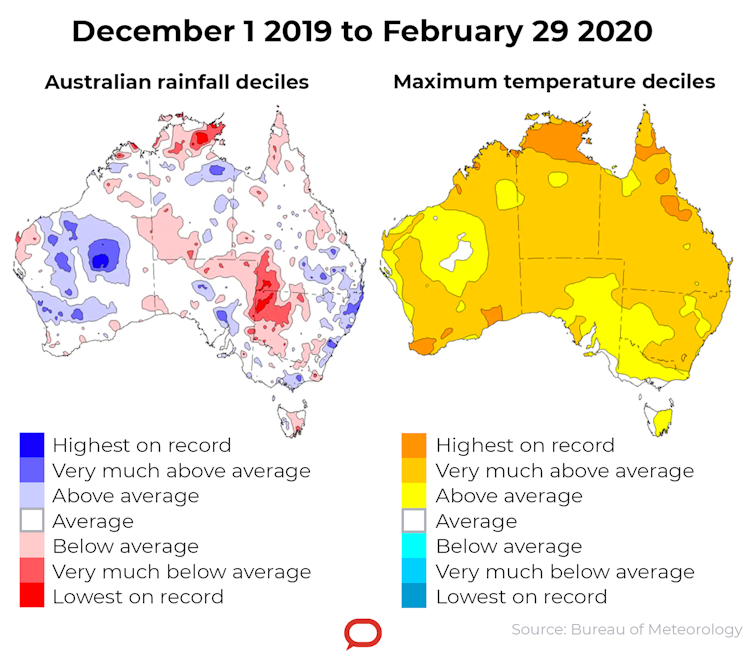

In the second half of the season, tropical moisture at times extended into southern Australia, producing well above-average rainfall for some areas. This was great news for many, but some parts of the country missed out. Other areas need follow-up falls over the coming months to ease the long-term dry, and inland water storages increased only slightly.

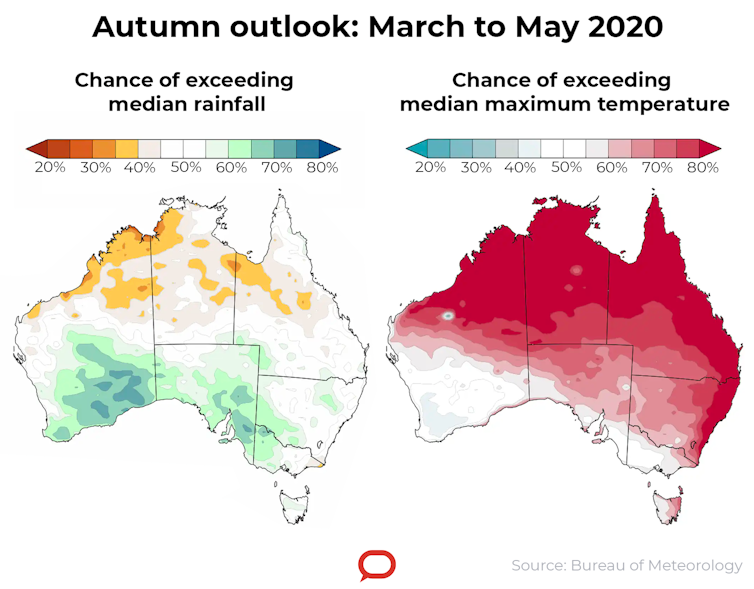

The autumn outlook suggests warmer-than-average temperatures for most of the country. There is also a slightly increased chance of wetter-than-average conditions in parts of southern Australia, indicating some areas could see a gradual easing of the drought conditions.

DAN HIMBRECHTS/AAP

What happened this summer?

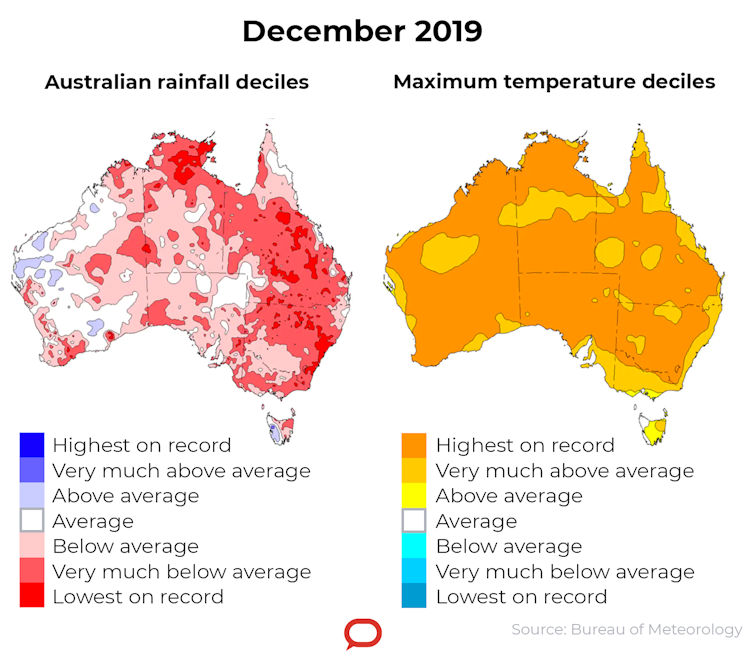

Summer 2019-20 was the nation’s second hottest in 110 years of records, driven in part by Australia’s hottest December on record in 2019. Warmth across much of the tropical north and east persisted into January and February. Summer nights were second-warmest on record.

Total summer rainfall was closer to normal – 8% below the long-term average. But the rainfall figures hide the significant shift in the climate mid-way through the season.

Australia experienced very warm and dry conditions in the lead-up to summer. With a delayed onset of the monsoon moving into the southern hemisphere, heat built across northern and central Australia from the start of December and was drawn south by weather systems.

Australia had its hottest day on record on December 18, with a nationwide average temperature of 41.88℃. This was far above the previous record of 40.32℃ set on January 7, 2013.

Six other days in December 2019 also exceeded this previous record. To put this in context, the Australia-wide average maximum temperature has exceeded 40℃ for

more days in the past two summers than in the preceding 110 years combined.

The hottest temperature recorded this summer was at Nullabor, South Australia, on December 19, when it reached 49.9℃.

Averaged across the continent, December maximum temperatures were 4.15℃ above

average – the previous December record was 2.41℃ above average, set in 2018.

Then the rains came

Early January brought a noticeable change to the weather, with the first tropical cyclones of the season and the belated arrival of the monsoon.

Tropical cyclones Blake and Claudia brought heavy rain to much of the Top End and northern and central parts of Western Australia, while the east coast saw heavy falls in northern New South Wales and southeast Queensland.

February brought more tropical moisture to the continent and another two cyclones—Damien and Esther.

Despite this, temperatures across the north remained very warm. The monsoon did not arrive until January 18, some three weeks later than normal, though almost a week earlier than the previous year. Even after the monsoon arrived it was sporadic, so did little to temper the heat.

The Darwin River Dam (Darwin’s main water storage) dropped to 54% capacity – the result of two relatively dry wet seasons in a row.

In contrast, in southern parts of Australia, February felt milder than normal. After Melbourne had three days over 40℃ in December – the most in December since 1897 – it had no days at all over 35℃ in February. This last happened in 1994.

What’s driving all this?

The abrupt change in weather patterns mid-season can be attributed to changes in two key Australian climate drivers: a strong positive phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD), and a negative phase of the Southern Annular Mode (SAM).

A positive IOD typically brings drier weather to much of southern, central and northern Australia. The 2019 positive IOD was the strongest since 1997 and affected large parts of the country (and eastern Africa) during the second half of the year. Normally such an event ends with the movement of the Asian monsoon into the southern hemisphere in late spring/early summer, but in 2019–20 this movement occurred about a month later than usual.

The delayed arrival of the Australian monsoon was likely related to the strength of the IOD itself, which prevented the monsoon’s southward shift.

The negative SAM typically brings drier and hotter than average weather to much of southeast and eastern Australia in spring and summer. It was triggered by a sudden warming of the stratosphere above Antarctica, identified in early September. This rare event affected Australian climate from October to December.

Both negative SAM and positive IOD are known to enhance the likelihood of increased springtime heatwaves and fire weather in southeast Australia.

In addition to these events, Australia’s changing climate underpinned the drier and warmer weather across southern Australia in winter and spring.

What to expect in autumn

Rain has eased the dry in some places, but more is needed. Most heavy rain was recorded east of the Great Dividing Range, while larger totals west of the range generally fell in regions that didn’t feed into water storages, or where soils were so dry there was little runoff into storages.

While Sydney’s water storages rose from 42% to 81% during the second half of summer, storages in the northern Murray—Darling Basin only rose from 6% to 12% – similar to levels at the height of the Millennium drought.

And while some areas had good summer rainfall, others missed out. Western NSW and southwest Queensland endured another dry summer.

The autumn outlook suggests parts of southern Australia have a slightly increased chance of being wetter-than-average, while scattered parts of the north may see a drier end to the northern wet season. Autumn days are likely to be warmer than average for most of the country, except for parts of southern Australia, suggesting evaporation will remain above average.

This outlook would indicate some areas could see a gradual easing of the drought conditions.

For more information, watch the Bureau’s March–May 2020 Climate and Water Outlook video and subscribe to receive Climate Information emails.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.