Uncertainty: The X factor behind more reliable streamflow forecasts

A new national forecasting service is giving dam operators, river managers – even kayakers – a clearer picture of river and stream flows up to a week in advance. Paradoxically, uncertainty is a key to more reliable forecasts.

Water – too little or too much of it – has always been a wicked problem for Australia. It’s a problem magnified by climate change in the form of extended drought and more intense storms.

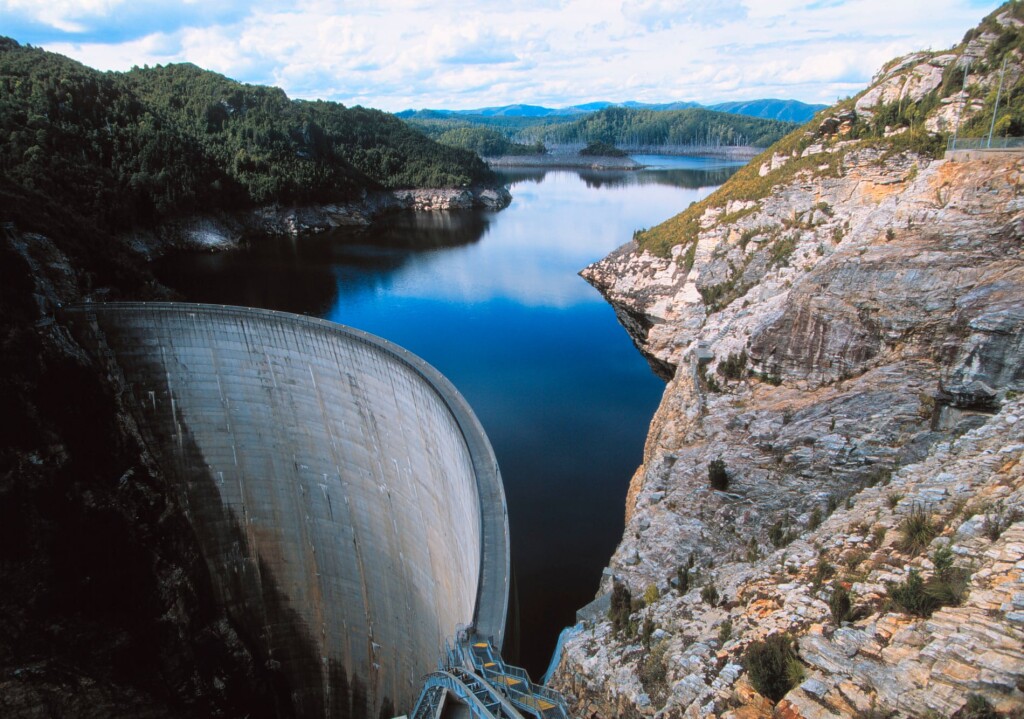

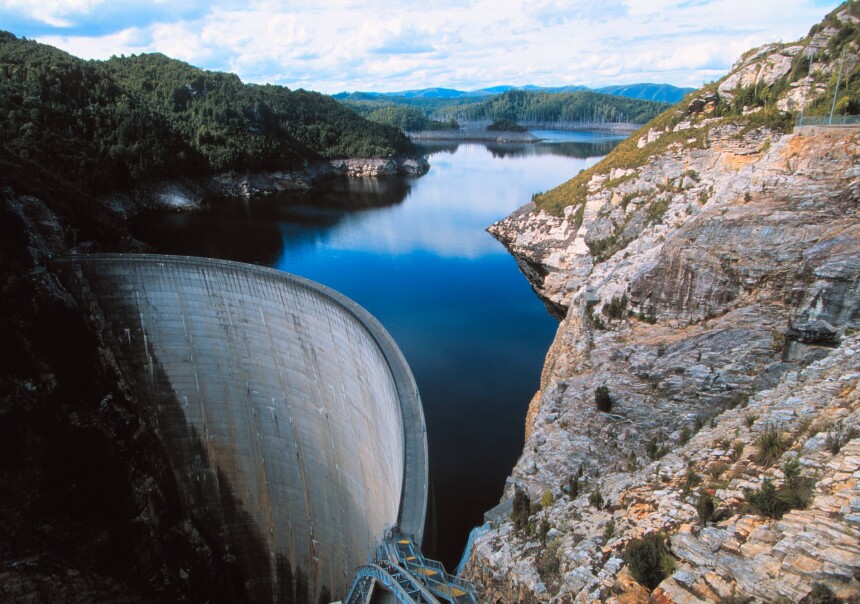

Yet every day, dam operators, river managers, irrigators, local governments – even recreational boaters and fishers – need to make decisions about how to best use the nation’s fluctuating inland water resources for water supply, agricultural, environmental and other purposes.

For dam operators, a poor decision about the timing and volume of a water release can put lives and property at risk. This is especially so if the dam is at near-capacity, the surrounding soil is already saturated, and heavy rain is forecast for downstream tributaries.

On the other hand, river managers face risks such as ‘wasting’ irrigation water releases if downstream tributaries flood in the meantime due to sudden storms.

With the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) recently confirming a La Nina event and above-average rainfall forecasts for eastern and northern Australia in late 2020 and early 2021, the increased flood-risk makes the job of managing catchments and water infrastructure that much harder.

To help dam operators, farmers and local government plan for the months ahead, BOM provides seasonal streamflow forecasts. It also provides flood forecasting and flood warning services to keep emergency services informed of hazardous river conditions after heavy rain.

Now, BOM is also providing Australian water managers with a seven-day streamflow forecast, developed in partnership with CSIRO, that offers more reliable estimates of river and catchment conditions up to seven days ahead.

The forecasts are publicly available via a BOM web portal.

Real-time updating, quantifying uncertainty

In contrast with existing forecasting tools, the modelling package behind the 7-day streamflow forecasting service gives a more fine-grained, hourly picture of how likely it is a river will rise or fall in the coming week.

The computer models simulate rainfall, surface runoff – based on how much water is already in the soil – and river flow. These simulations are updated regularly with real-time data from BOM’s national network of rain and river-flow gauges.

Key to the accuracy of the 7-day streamflow forecasting tool is the way it quantifies uncertainty. This, and the daily updating, set this tool apart from existing ‘deterministic’ forecasting tools, which produce single, hourly streamflow estimates once a day.

“The 7-day streamflow forecasting is not just saying that for the next seven days, the streamflow will be a particular value,” says CSIRO’s Dr David Robertson, who developed the statistical methods behind the forecasting tool. “Rather, it’s acknowledging there’s some uncertainty in that prediction. That’s useful, because when we start to think about five to seven days ahead, we really don’t know precisely how much rain is going to fall, and how much of that rainfall will translate into streamflow.”

Ensemble forecasting

The incorporation of uncertainty into forecasting models is a capability developed by BOM, in line with other major weather forecasting facilities around the world. Instead of making single-value forecasts of the most likely weather, an ensemble or probabilistic forecast produces a set, or ensemble, of forecasts.

This ensemble describes the range of possible future weather conditions and accounts for errors introduced by the chaotic nature of atmospheric systems, and errors related to the imperfections of the forecasting model itself.

The result is a set of forecasts, each with a predicted ‘spread’ of possible highest and lowest levels for that interval. The amount of spread is related to the uncertainty or error of the forecast.

“With a deterministic forecasting system, you have a single streamflow forecast,” says Dr Prasantha Hapuarachchi, who is the technical lead for implementing the streamflow forecasting service at BOM. But, for example, is there a 50% probability of exceeding a certain streamflow threshold in a few days? Or a 1% probability the flow will not go above the threshold later today?

“That sort of information is really valuable for risk-management. Dam operators want to know how much flow is coming into a reservoir from upstream so that they can plan water releases safely and efficiently.

“If there are natural flows coming into the main river from tributaries downstream, they may be able to save that water.

“For all of these sorts of operations, they need to be able to plan five to seven days ahead.”

Longer lead times, better outcomes

CSIRO’s James Bennett believes the longer lead times are critical for users of the streamflow forecasting system, which starts with hydrological modelling to estimate the ‘wetness’ of soil in a catchment, which he describes as a ‘giant sponge’.

“We work out how much water is in the soil with a simple hydrological model, which we ‘spin up’ [the process of initialising or stabilising the model] so that it produces an estimate of soil moisture. Once we’ve got that, we just add the rainfall forecast in.”

While BOM only introduced the new forecasting service in June for 209 locations across the country, Mr Bennett says the team hopes to see it more widely used for water and environmental management decision-making.

The Murray-Darling Basin Authority is already using the service to plan and time environmental flows upstream of Lake Mulwala, and it is also being used to manage environmental flows in Victoria’s Goulburn Broken catchment.

Next steps for streamflow forecasts

Dr Paul Feikema, who runs the 7-day streamflow forecasting service at BOM, says the team is currently working on making the ensembles available via FTP transfer so that users can ‘plug’ the forecasts directly into their own models.

“It’s a fairly new service, so we’re working on increasing the adoption,” he says. “We’re working closely with stakeholders and customers and getting a better feel for the decisions they make.”

Dr Hapuarachchi says BOM is now investigating how to implement ensemble technology for its flood forecasting services.

Flood forecasts are issued by BOM after heavy rainfall, when floods are anticipated, and key client agencies include emergency services, such as the SES.

Mr Bennett believes the ‘ensemble’ approach could make it easier for managers who are not specialists to understand streamflow forecasts.

“Currently, a lot of flood forecasting at BOM is manual. BOM has a lot of highly trained hydrologists who develop the flood forecasts – they tune their models in real time. It’s called ‘in the loop forecasting’, and it really does allow them to communicate directly with emergency services managers about what’s going to happen.

“That’s a tremendous benefit, but it’s also labour-intensive. If you want to expand the service, it’s not so easy. It takes a long time to train hydrologists to understand the uncertainty in these forecasts, and to be able to issue them. But our methods automate this. They automate the estimation of uncertainty.

“In theory, you could expand it to areas where, previously, it wasn’t worth setting up a forecasting service, such as for new water infrastructure. That would allow you to get more value out of the asset, because forecasting services, in comparison to major infrastructure, are often cheap. They could be a low-cost way to maximise the value of investment in water infrastructure.”

Originally published by the CSIRO, 1 December 2020.